Two Cranes in One Day

by

Jason Erik Lundberg

The

scene is a classic one:

a heroic cowboy steps out onto the dusty main street, his

spurs clanging, his jaw set, and he faces his nemesis. As

they stare each other down, a tumbleweed blows across the

road, and the onlookers hold their breaths. Time seems to

stop in that perfect moment of anticipation, the combined

concentrations of our hero, his nemesis, and the onlookers

calcifying the moment into temporal stasis. Someone gasps,

and either the hero or the nemesis twitches, it doesn’t

matter who, then both men draw their guns and fire.

On a

bitter mid-December morning in North Carolina, I was that

cowboy, facing down my nemesis. Only, instead of a grizzled,

world-weary, dark-hearted gunman, my showdown was with a printer

named Carl. His eyes were beady and his cologne smelled of

rancid tar. The overheated print shop we stood in caused a drop

of sweat to trickle down between my shoulderblades. The air

reeked of toner and inks.

Carl’s upper lip twitched. It was the signal.

We

both drew our weapons.

I

was faster.

My

second year of graduate school, I decided to publish an

anthology with my wife Janet Chui. We’d had some fun putting

together a chapbook of our fiction, artwork and poetry the

previous year, and the copies had sold well. On the success of

that small book, called Four Seasons in One Day, we

wanted to put together a collection of other people’s fiction.

Many of our writer friends were doing it—specifically couples,

like Gavin Grant and Kelly Link, Christopher Rowe and Gwenda

Bond, and Tim Pratt and Heather Shaw—so why not us? Instead of a

zine, we decided on an anthology, which would allow us to

publish more stories and sell the book in bookstores.

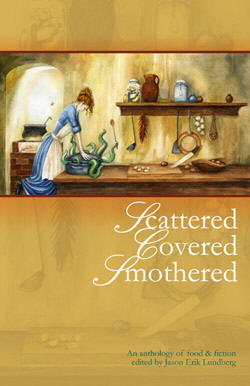

Our

theme was food, and we decided to call it Scattered, Covered,

Smothered.

I

wrote up the submission guidelines, and pestered everyone I knew

to send me stories. We ended up with twenty-two short stories,

five poems and eleven recipes, with contributions from Jeff

VanderMeer, Nalo Hopkinson, Barth Anderson, Rhys Hughes, Toiya

Kristen Finley, Bruce Boston, and many others. We had ourselves

an honest-to-Buddha anthology.

As

editor, I was in charge of choosing the stories and shaping the

book (with much consultation from Janet), and Janet was in

charge of the cover art and the book design. Once she had

finished the arduous task of taking all the disparate

contributions and laying them out into a consistently styled

book, she found a printer in town that could produce 230 copies

in about a week. We had already gotten the covers printed by a

fantastic online printer, so all this new printer (called IMP)

would have to do was the interiors, and then the binding for all

the copies. We compiled the files into one PDF file, and dropped

off a CD to IMP on a Friday afternoon.

The

following Tuesday, I got the phone call: “Your proof is ready.”

I

left work early, drove the twenty minutes to downtown Raleigh,

parked in the deck down the block, and, bounce in my step,

walked into IMP. Standing at the counter was Carl, the man we’d

dealt with over the phone, holding a copied and bound proof copy

of Scattered, Covered, Smothered.

“Hi,” said Carl. “You sure got here fast.”

“Well, this is pretty important,” I said.

Carl

smiled. “Here it is, take a look.”

On

first glance, it looked fantastic. The pages had all come out in

good quality, and had been trimmed to the size we wanted,

half-letter, or 5.5” x 8.5”. The stories were all in the right

order. It was a book.

But

then I looked at it again. The graphics that Janet had used on

the contents pages and the recipe pages were fuzzy. In fact,

they looked downright terrible. Intended as corner borders for

these pages, the graphic was of an orthogonal grapevine, which

fit in with the whole idea of food-related fiction. But the

images looked as if the resolution had been downscaled.

And

as I turned back and forth between the pages, the paper got

stuck in the binding. We had chosen a twin-loop wiro binding to

continue the food motif, since it is the style used by many

publishers of cookbooks, but as I turned the pages, it quickly

became obvious that the diameter of the loop was too small.

Pages caught on other pages, making the turning difficult. Not

only that, but the loop was not closed completely in the back,

meaning that the last few pages kept slipping from the binding

and falling out.

I

mentioned these problems to Carl, but all he said was, “Huh,” as

if I had just pointed out a thoroughly unremarkable insect. In

an attempt to remedy the page slippage in the back of the book,

he compressed the loop from a circle into an oval, making it

even harder to turn the pages.

“Oh,

don’t worry about that,” he said. “We’ll fix it later.”

When

I asked about the fuzziness of the graphics, Carl shrugged and

said, “That’s just how it came out.”

“Did

it occur to you that maybe fuzzy graphics are not what we

wanted?”

He

shrugged.

At

this point, I was seriously wondering if we had made a big

mistake in choosing these people to put our book together. I was

feeling the pressure of deadline; I had promised the people who

preordered the book through our website (twocranespress.com)

that they would receive the book by Christmas. I thought we had

left enough time, but the process of getting rewrites back from

our authors, and sending out contracts and payment, had eaten

into our production schedule, and we were getting crunched for

time. The reputation of Two Cranes Press, our small press

publishing venture, was on the line. If I decided to withdraw

the book from IMP, it would mean pushing back our release date

and reneging on our promise.

“Look,” I said, “I need to show this to my wife, since she

designed the book and has a very specific look she wants for it.

Please don’t run anymore copies until I get back to you.”

“All

right,” he said.

I

left. There were some recommendations for PhD programs I needed

to drop off at the NCSU campus to my professors. Two of them,

John Kessel and Wilton Barnhardt, were in their offices and I

showed them the proof copy. Despite the problems, I was still

excited about it being a book, and they both agreed that it was

a neat idea.

When

it was time to pick Janet up at her day job across town, I drove

the half-hour to her work and showed her the book. She was very

quiet at first, turning the pages, cringing at the fuzzy

graphics, noticing the bunch-up of pages as she turned them. She

then made her objections very vocally clear, the same ones I’d

had about the binding and the graphics.

“This looks like shit,” she said. “It’s a good thing I wasn’t

there today or I would have jumped over the counter and

strangled that guy. Why the hell didn’t he call us?”

I

said I didn’t know.

Most

of the rest of the ride home was in silence, a sure sign that

she was deeply unhappy. When we got home, she sat on the sofa,

paging through the book over and over, getting more and more

upset. At one point she stood up and said, “I want to see the

files.”

I

booted up my computer and brought up one of the PageMaker files

that included the graphic that had printed out as fuzzy from the

printers. Janet had me print out the page directly from

PageMaker, and the clip art came out sharp and crisp. Which

meant that something had happened to the image between the

completion of this file and the page produced by the printers.

We’d had to convert the entire book to PDF (portable document

format) so that the printers could read it, so I brought up that

file and printed off a page. Fuzzy.

Janet got on her own computer and dug around on the internet,

looking for an explanation. She discovered that our version of

PageMaker (6.5) downscales images to 72 dpi (dots per inch; i.e.

screen resolution) when files are converted to PDF. It was a

glitch that nobody seemed to know what to do with; no patches

were available online. Janet fiddled with files for a couple of

hours, trying to trick the software into doing what she wanted,

but to no avail. So our options were twofold:

1.

Either upgrade to PageMaker 7.0, which wasn’t an

option; publishing the book ourselves was very expensive, and we

just couldn’t afford one more expense; or,

2.

Find another format for the images so that they

wouldn’t be downscaled.

By

this point, Janet was fed up with everything, mostly with the

attitude and service of the printers. She had had excellent

dealings with the printers in Singapore for various projects,

but most notably for Four Seasons in One Day. She had

completely laid out that book as well, and the printers there

had kept in contact with her over the production of the book to

make sure it was exactly what she wanted. Compared to that, Carl

just didn’t seem to care.

She

went out to the living room, and I looked at the files some

more. The images that had been used were jpegs, a raster-type

image format that uses pixels. But she had also saved the images

as EPS files, which is a vector-type format that uses entities

like lines and circles that don’t change if you alter the size.

This was the solution. I started replacing the images in all the

files that contained the graphic with their EPS versions. There

were a few other proofreading goofs that I’d missed, so I fixed

these as well. It would take most of the night, and I’d have to

reconvert everything, but it looked like the book could be

saved.

I

walked out to the living room to tell Janet what I’d discovered—

Okay, I have to stop for a bit here. I have a confession to

make: the account I’ve been relaying is not entirely accurate.

The events I’ve described are as close to what I can remember as

I can convey in words, but my part in them is slightly

different. It’s hard to admit when you’ve made a mistake. It’s

difficult to admit your limitations. However, it’s very easy to

alter events slightly to put a better spin on yourself. I keep

an online journal, and you can check in the archives what really

happened, so it’s easy to check the facts. It’s not fair to you,

gentle reader, to give an untruthful account.

When

I saw the proof at the printers, I thought it looked great. I

noticed the fuzziness of the graphics, but it didn’t seem like a

big deal to my untrained eyes. I figured that Janet and I would

notice, but that it really wouldn’t be that big a deal to anyone

else. The binding was a problem, but I didn’t really bring it up

with the printers; I figured it would get fixed when they did

the actual binding. I didn’t hold them up to a high professional

standard like I should have. If we had put out the book like

that, it would have been sub-par, and it would have been notched

up to amateurishness. We would have gotten a reputation as a

small press who doesn’t give a damn about presentation, when

this is far from the truth.

I

indeed told Carl that I needed to show the proof to Janet, but I

neglected to tell him to stop printing on the book. This would

turn out to be a slight problem later. Again, I was blinded by

scheduling pressures, which might have resulted in a poor

quality book. By that point, we had sold half of our print run

in preorders, and I just wanted to get them out the door.

This

is part of why Janet was so upset. As the graphic designer and

cover artist for the book, she had (and has) a keen eye for

detail, and the first thing she looks for is the flaws. She was

frustrated by the printers for their lack of communication and

shoddy work ethic. But she was also frustrated that I couldn’t

see what was wrong as much as she could, that I wasn’t nearly as

outraged as she over the condition of the proof. I didn’t “get

it” in her eyes.

Like

I said, it’s hard to admit your own failings. I was excellent at

the marketing and promotion of the book, but when it came to

design decisions, she just couldn’t count on me. Part of that

evening, while I changed all the files and recompiled them, was

spent vowing that I would fix things. I had let Janet down, and

some part of this had caused her emotional distress, and I felt

terrible for it. With each fix, I was trying to make things a

little better, to make up for my limitations.

Once

I realized that I could substitute the EPS files for the jpegs,

I walked out to the living room to tell Janet what I’d

discovered. She was bent over the proof copy of the book,

turning pages, and sobbing. I tried to console her, tell her

that it was fixable, but she was so frustrated and upset over

the whole thing that all I could really do was sit next to her,

rub her back, and let her vent her disappointment. I remember

the warmth radiating from her, as if her anger and frustration

had transmuted to heat within her body. She didn’t come to bed

that night, spending it instead on the couch, the first night we

slept apart since we’d been married.

I

stayed up until 1:00 a.m. getting everything finished and

recompiled into a new PDF. I burned it, and all of the source

files, onto a CD, so that I could take it back over to the

printers first thing in the morning. I left phone and email

messages telling them to stop printing, in case they had

started.

Sleep was fitful that night. I was alone in the bed, and my

thoughts raced. My neck and shoulders were bunched tight from

the stress. A project that we had thought would be fun four

months earlier had turned into a monumental hassle.

The

next morning, Wednesday, we got ready, and I took Janet to her

day job across town. I called my boss from my cell phone and

told her I wouldn’t be in that morning because I had to deal

with the printing nightmare; having dealt with printers before

herself, she could empathize. The drive downtown increased my

anger at what had happened, and by the time I had parked the car

and walked to IMP’s offices, I was seething. Nobody would be let

off the hook.

A

different clerk was standing at the counter, so I asked for

Carl. He came out of the back room, looking unhappy to see me.

Apparently, he’d gotten my messages. His eyes were beady and his

cologne smelled of rancid tar. The overheated print shop we

stood in caused a drop of sweat to trickle down between my

shoulderblades. The air reeked of toner and inks.

Carl’s upper lip twitched. It was the signal.

We

both drew our weapons.

I

was faster.

“After talking with my wife,” I said, “we’re really not happy

with this book.”

“I

wish you’d told me this yesterday,” Carl said.

“Why?”

“Because we already ran 75% of the print run.”

“What?”

“You

said it looked fine.”

“I

said I needed to show it to my wife.”

“But

you didn’t tell me not to run the copies.”

I

stood back and controlled my breathing.

“Well, look, I’m not paying for them. You saw the fuzzy graphics

yesterday. Why didn’t you call me about that?”

He

looked away and shrugged.

“Look,” I said. “This quality is terrible, and we’re not paying

for it. I brought you a new copy of the PDF file to use.”

After some more back and forth, him trying to get out of any

responsibility, he finally agreed to eat the copies. Fantasies

of making him literally eat the copies flitted through my head.

I gave him the CD, and he did a test print to make sure all the

graphics came out all right. They did, and I sighed in relief.

I

then explained the problem with the binding, the too-small

diameter, and showed him the condition of the proof copy, which,

at that point, looked as if a dog had mistaken it for a ribeye

steak. He agreed that it wouldn’t do, but the only size wiro

binding they had in stock was that size. If he had to order the

next size up, it would take another week, unless he got it

overnighted from the supplier. He said he could also contact the

local binderies to find out if they could get it done by Friday,

which was when we needed it. He asked me to give him a couple

hours.

I

walked down the block to the coffeeshop on the corner, sparsely

populated after the morning rush. After ordering a chai, I sat

at a table and called Janet to update her. She had calmed down a

bit, and seemed to have faith that I was getting things done.

She gave me the number of a bindery in town that might be an

option; if IMP couldn’t get the printing and binding done

by Friday, then maybe we could get the copies from them, and

have the books bound elsewhere. I called the bindery, and they

said they could do it, but that I’d have to get all the copies

to them by 7:30 a.m. the following morning.

I

read the USA Today on the table in front of me cover to

cover, breathing deeply, and generally trying to settle my

nerves. After the initial discussion that morning, Carl seemed

to want to put things right and work with me on fixing the book

and getting it done when he originally promised it would be.

After the two hours were up, I walked back down to the printers.

Carl had made a deal with a local bindery, and all the books

would be completed—copied, collated, bound, and delivered—by

Friday afternoon. I mentioned the other bindery I'd called, but

he said the copies wouldn't even be done until the following

afternoon, so that option was out.

“We’ll get everything done and to you when I originally said we

would,” he said. “Trust me.”

“I

hope you can understand why it’s hard for me to do that,” I

said.

“I

understand.”

“You

haven’t really engendered a whole lot of trust up to now.”

“I

know. But we’ll fix everything and get it done by Friday. I

promise.”

I

took a deep breath. I was putting the book back in their hands.

I was having to put my faith in their abilities and in the karma

of the universe in the hopes that there would be no more

screwups, that everything would turn out right and on time.

“Okay,” I said. “All right, I’m trusting you to get it done. If

you run into any more problems, no matter how minor, please keep

in touch.”

“You

got it.”

I

called Janet from the car on the way to work and told her that

everything had been taken care of, and, hard as it was to

accept, it was out of our hands now. We really had no choice but

to hope for the best.

Those twenty-four hours were an extreme test of patience and

conviction. It was the most upset I had ever seen my wife, and

short of stabbing Carl in the eye with his own tie-tack, I would

have done anything to make the situation right. It was also

extremely difficult to realize that I was not in fact a

jack-of-all-trades, that I had limitations when it came to my

own design sensibilities. It was a test of our marriage as well,

whether we could survive the collaboration of a publishing

project.

Ultimately, everything ended well. The finished books arrived at

2:30 on Friday afternoon, delivered by the printers right to our

front door. All the bindings had been fixed to the right

diameter, and the loops were closer together with square holes,

which was what we wanted in the first place. The pages turned

easily. The graphics were sharp and clear. It was only December

17, but in my book, this was a Christmas miracle. Carl had come

through for us; he’d stepped up (eventually) and produced the

book that we wanted.

We

spent that night boxing up all the preorders, review copies, and

contributor copies, and mailed them out the following morning.

Most of them reached their destinations by Christmas, just like

we promised. Since that time, we have nearly sold out of the

book, with some very positive reviews in Locus, The

Agony Column, and Emerald City. (Another is

forthcoming from Realms of Fantasy.) As of this writing,

only fifteen copies out of our original print run of 230 are

still available.

So

fellas, a word to the wise: listen to your wives or girlfriends.

Not only is Janet exponentially smarter than me, but she knew

what needed to happen with the book so that it could compete

with books by the big publishers. Her unflinching vision of

quality is why the almost universal reaction on seeing the

anthology is, “This is so beautiful!” And for my efforts in

dealing with the printers, she gave me an iPod for Christmas,

which was a very nice bonus, and very happy ending for yours

truly.