Why

I like nudibranchs,

marine slugs with

Verve

by Hans Bertsch

author of

"Everything

you ever wanted to know about nudibranchs but were too timid

to ask"

Hans at Bahía de los Angeles

(copyright

©

Jim Mastro)

Some

thirty-five

years ago I was living at the Old Mission Santa Barbara,

California, undergoing theological training to become a Catholic

Franciscan priest.

There is a museum, down and

across the canyon from the mission —

the Santa Barbara Museum of

Natural History. The director of the invertebrate zoology department was

Mr. Nelson Baker. He smoked the biggest, thickest, longest,

most humongous cigars available. And back in those days, he

didn’t have to go outside under a tarp like California’s

Governator today.

Hans at Bahía de los Angeles

(copyright

©

Jim Mastro)

Some

thirty-five

years ago I was living at the Old Mission Santa Barbara,

California, undergoing theological training to become a Catholic

Franciscan priest.

There is a museum, down and

across the canyon from the mission —

the Santa Barbara Museum of

Natural History. The director of the invertebrate zoology department was

Mr. Nelson Baker. He smoked the biggest, thickest, longest,

most humongous cigars available. And back in those days, he

didn’t have to go outside under a tarp like California’s

Governator today.

One of

the staff members was a gentleman named Gale Sphon. He sort of

took me under his wing, allowed me to do some part time work

at the museum, and in general helped a fledgling scientist.

I would meet him at 3 am, and drive

50 miles or so northward to Punta Concepcion, where he had

obtained special permission to collect. We had to pass through

several locked gates. (Not only is it private property. It is

adjacent to the Vandenburg military station, which frequently

shoots rockets off across the Pacific to near Enewetak, to make

sure their guidance systems work. Good idea.)

Here we'd be, using flashlights and

lanterns, in pitch total blackness, wearing thigh-high rubber

protective boots.

We'd squint and squeeze our eyeballs

looking for 5-15 mm long slugs, often very well camouflaged.

Then, like the beginning scene of “2001, A Space

Odyssey,” there'd be a sudden moment of enlightenment as the sun

rose and cast its light onto the tide pools. What had been

only outlined by our narrow beams of light, was now brilliantly

revealed in a full kaleidoscope of color. The algae reflected

marvelous shades of brilliance — green, a blue glow, reds . . . The tide pools exploded in a brilliant rainbow

destroying the darkness with iridescent coloration.

Then we started to find more and more

nudibranchs

(pronounced

nu-di-brank)

—

in pinks, whites, yellows, oranges, blues, and all

sort of shapes and sizes!

Gale and I would work the low tide site

another hour or two, until the low tide became slack, and then

reverse to come back in and cover our search areas. But we

were satisfied, took our bucket of unidentified species back to

the museum, and placed them safely in an aquarium. He'd go home

and I'd return to the Mission to take a nap, until we would

regroup later in the day to identify the species (unnamed, range

extensions, well-known, etc.) with the museum’s microscopes (and

Mr. Baker’s cigar).

That galvanized my interest in

nudibranchs — to go from pitch blackness in the field to the

elegant beauty of sunshine in the morning!

From there it did not take me long to

really get hooked on nudibranchs. I took a summer invertebrate

zoology course, had to do a research project — and guess what I

chose? The interactions between a nudibranch and its

cnidarian prey!

The rest, as they say, is history.

The joys of discovery,

and naming

I

published my first scientific article (in The

Veliger) in

1969, and named my first species of nudibranch in 1970.

. Glossodoris baumanni

(copyright

©

Hans Bertsch)

Glossodoris baumanni

(copyright

©

Hans Bertsch)

This was a real milestone, because it

was the first species of nudibranch ever named that used

scanning electron microscopy to illustrate the radular teeth!

-

Radular teeth

-

Glossodoris baumanni

(copyright

©

Hans Bertsch)

The species was collected while I was

working at a marine station near La Paz, Baja California Sur,

under the directorship of Dr. Rita Schaefer of the Los Angeles

Immaculate Heart College. Just an aside, we stayed at the

resort home of

Bing Crosby!

(Ed: HB

disingenuously puts an exclamation mark after this comment, but

the connection between

scientists

[especially the slug-smitten

subspecies nudibranchologist]

and Bing deserves exploration.)

This species was named in honor of

Father Anthony Baumann, my high school biology teacher who was

so important in my formation as a biologist.

This recent article by Terrence Gosliner and myself,

describes three species of Okenia nudibranchs

from the eastern Pacific

and the coasts of Baja California that we discovered and named.

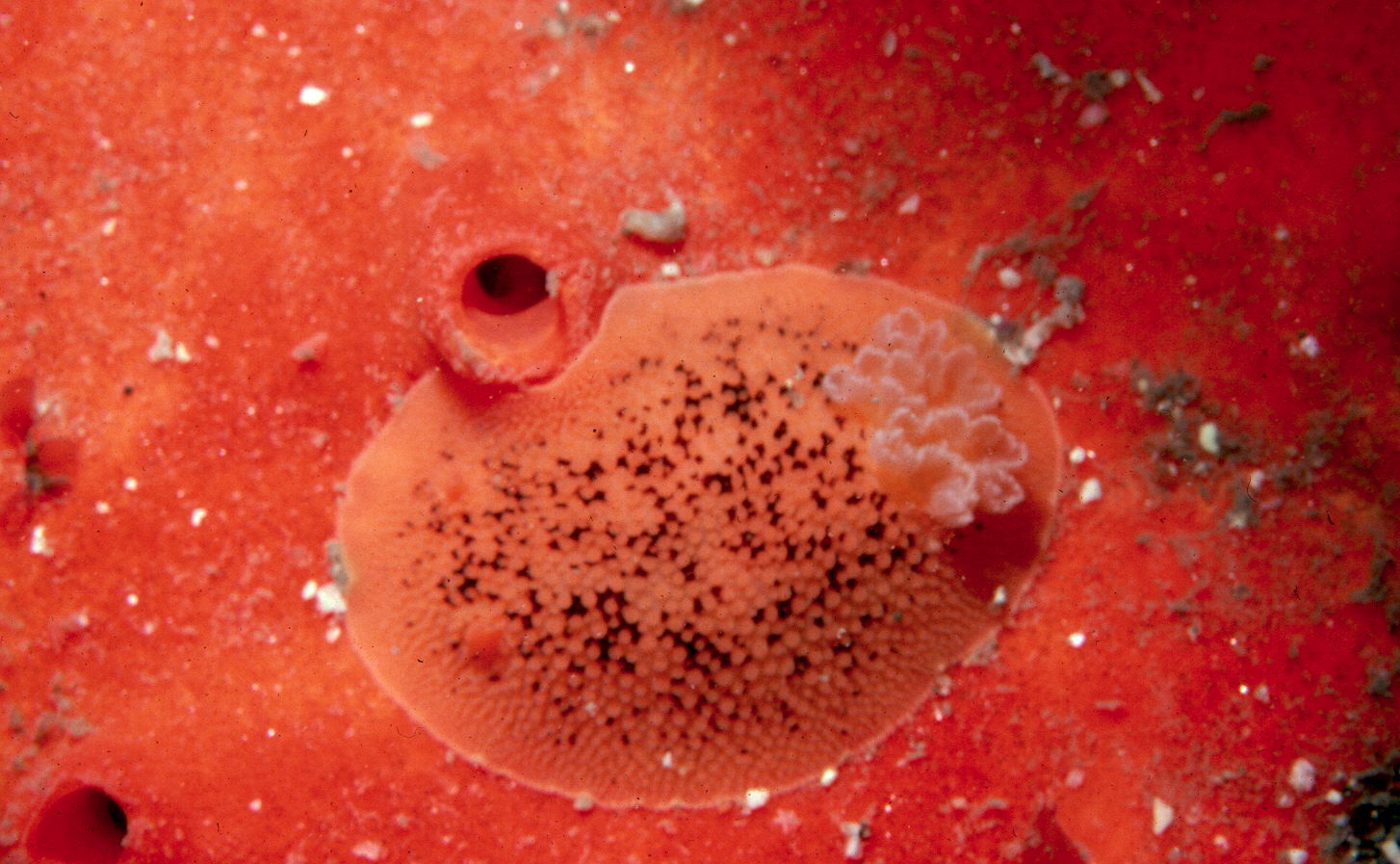

Chromodoris marislae

(copyright

©

Hans Bertsch)

Chromodoris marislae

(copyright

©

Hans Bertsch)

The Chromodoris

marislae is more common in the

southern Gulf of California, although this photograph was taken

at Bahía de los Ángeles.

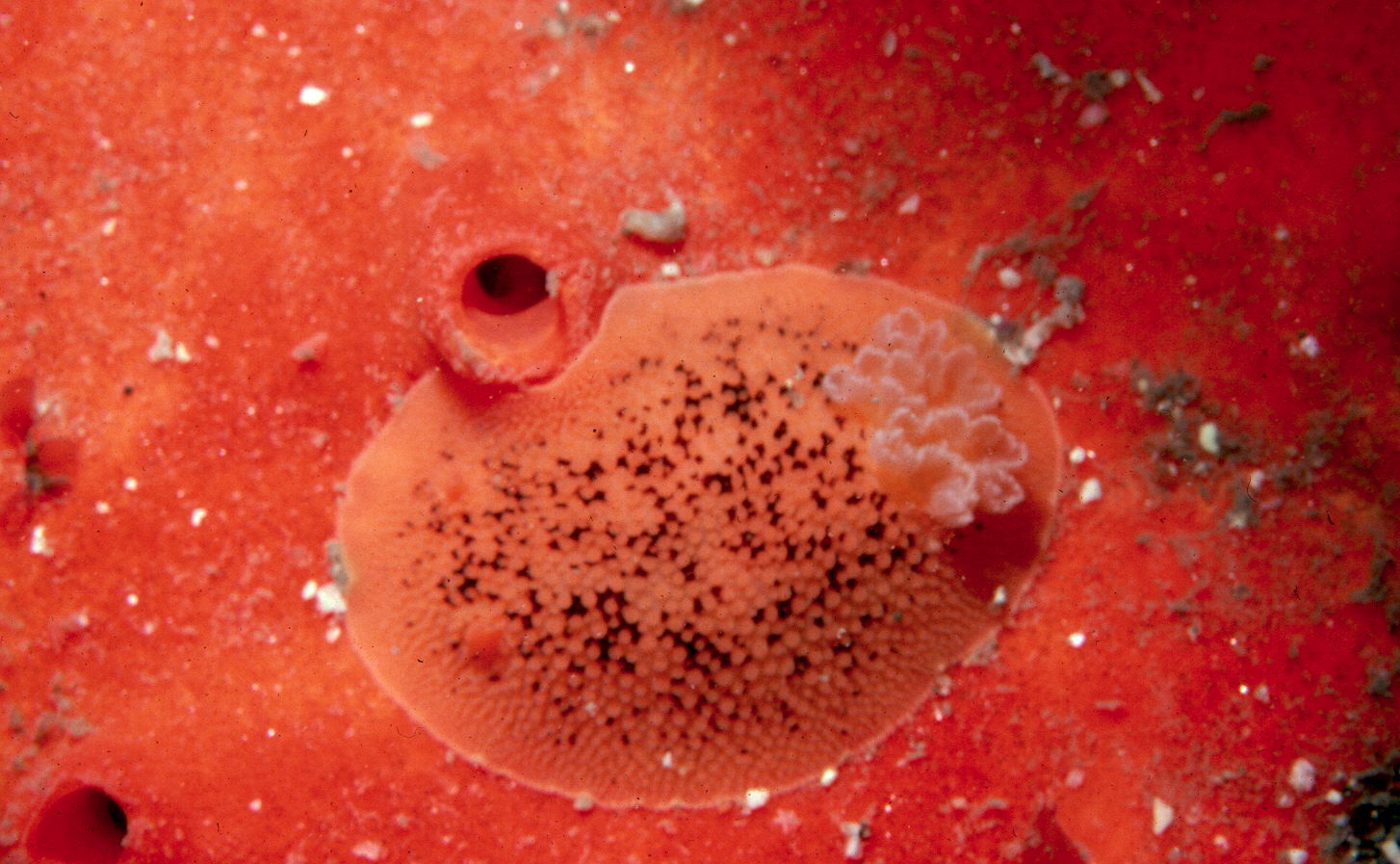

Peltodoris nobilis

(copyright

©

Hans Bertsch)

Peltodoris nobilis

(copyright

©

Hans Bertsch)

This specimen of

Peltodoris nobilis

is intriguing, because the animal is usually yellow with black

maculations, but it has been feeding on an orange sponge which

affected its coloration.

Fascinating party

animals

Biologically, nudibranchs and their related opisthobranchs are

incredibly interesting animals — showing camouflage, chemical

defenses, and all sorts of other defensive mechanisms.

Besides, they are beautiful, all dressed up ready to party!

Enjoy the animals, and their names!

Go take pictures of them!!!!!!!

Ed. note: Dr. Bertsch never mentions their rather amazing sex life here, but he does

in his renowned exposé,

Everything you ever wanted to

know about nudibranchs

but were too timid to ask

Dr.

Hans Bertsch was born in St. Louis, Missouri, and received

his Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley. His many

publications include technical works on archaeology, the

philosophy of science, marine biology, and popular scientific

articles on various natural history topics. He has published in

Mexican, Japanese, Israeli, German, Norwegian as well as U.S.

journals.

He has named over 30 species of nudibranchs, and has had

several named in his honor. His favorite is Bajaeolis

bertschi, foudroyantly colored in various shades of pink and

red, with white maculations.

When not underwater, preparing lectures, or writing, he

enjoys meandering the dirt roads of the Baja California

peninsula, plant, animal, and rock art hunting.

AT:

on Hans Bertsch Although he has written many technical

works of great erudition, his ability to communicate his love of

the creatures he studies, and his respect for their world, are

extraordinary. I was besotted with sea slugs before I read

"Everything . . ." but with a bit of knowledge and a lot of his

enthusiasm, my awe has grown, with lots more curiosity.

He has infected me with the wish to know more, which is what

science and communication should be all about. I hope he continues

to explore, and to write more for those of us who have

never seen a courting nudibranch, let alone seen a writer, let

alone a scientist, so casually use the word "foudroyantly."

Dr. Hans Bertsch may be

contacted at:

hansmarvida (at) sbcglobal.net

Chromodoris marislae

Chromodoris marislae